Books

Adventuring in Australia by Eric Hoffman

Sierra Club Books/Random House, San Francisco, First Edition 1990, 482 pages ISBN 0-87156-742-3

Adventuring in Australia by Eric Hoffman,

Sierra Club Books/UC Berkeley Press, Second Edition 1999, 514 pages, ISBN 0-87156-961-2

A natural history guide: Adventuring in Australia is primarily a guide to the wild areas of Australia, with an attempt to explain what lives there, how it survives, and where to find it. The emphasis is on animals but the plants and ecosystems that help sustain them are often discussed. There is also a sincere effort to explain the history, beliefs, art and music of the first Australians, the Aborigines, European settlement, and contemporary Australia.

Aussie government endorses the project: The book was perhaps the first attempt at a nationwide look at Australia’s natural history written as a guide for tourists. The natural history focus and breadth of the effort drew the support of the Australian government who supplied me with both domestic and international airline tickets.

Aussie conservationists & scientists make it a better book: As a project Adventuring in Australia was ridiculously underfunded, but made possible by the hospitality of Australians I met along the way. By the time the research part of the project came to an end I had convinced myself that Australia is a finalist for best country in the world. I’ll never forget the hundreds of interviews and meetings set up for me as I worked my way through cities and remote areas. Amazingly I was never stood-up, not once. Everyone met me where and when we had agreed. These rendezvouses were often down long rutted dirt tracks in places like Kakadu National Park in the Northern Territory or the Gibb River Road that transects the mostly uninhabited (by humans) Kimberly region of Western Australia. There were many dramatic meeting places: the big vista kangaroo-rich desert parks in New South Wales, the giant sunrises and sunsets on the stark Nullarbor plain, pock-marked by gigantic gopher-like holes made by Southern Hairy-nosed wombats (Lasiorhinus latifrons); cross-country skiing through twisted snow gums in the Victorian Alps while bright red Crimson Rosella (Platycorcus elegans) landed in the snow and strutted around us looking more like Christmas ornaments than a birds, the ancient Aboriginal art galleries in Kakadu National Park, and scuba diving on the Great Barrier Reef where the number of colorful corals and fish is overwhelming. I could, and did, go on for pages.

Survival strategies in an ancient land: Australia is an ancient land. For the most part evolution there has been isolated from other continents for millions of years. For creatures in the interior avoiding the heat and making the most of limited moisture is the constant in survival strategies. This is partly why 60-pound Southern hairy-nosed wombats (Lasiorthinus latifrons) live in vast tunnels underground, and most predators prefer to hunt at night. The avian wildlife is stunningly colorful and habitually loud.

Visitors are often surprised when they step out of a car in the vast, mulga scrub in the southern half of the country. They expect silence. Instead, they usually get a chorus of noises as parrots and other types of birds of all sizes and descriptions go about their business. As a visitor peers into the scrub to locate what’s making the noise they see flashes of color as dozens of different species move through the bush.

Bird species galore: Australia is in a class by itself when it comes to varieties of cockatoos, lorikeets, honeyeaters, kingfishers, and two kinds of ratites: the emu and cassowary. There are also many species of wetland and sea birds. Nearly 700 species of birds nest in Australia. The bird experience can be mind- boggling. I’ll always remember the time sleep was made impossible in my one-man tent under some huge River Red Gums (Eucalyptus camaldulenis) in Mutawintji (formerly Mootwingee) National Park. I was the only visitor that night. Just as the sun was setting thousands of Little Corella cockatoos (Cacutua sanguina) suddenly descended to perch in the trees over my head. These shiny white parrots with blue mascara-like patches under their eyes spent the moonlit night in non-stop squabbling, cartwheeling, and screeching. Their noise was literally deafening. They were so loud that two people standing next to one another screaming at the top of their lungs wouldn’t be heard. In the course of the night the birds stripped the leaves off three immense River Red Gums. With the dawn, the flock spiraled upward like a huge white tornado, on its way to the next resting place.

Expect secretive nature: Terrestrial life forms are much more furtive than the birds whose colors and noises can’t be missed. Even the largest terrestrial predators have mastered stealth and silence. During a night outing on the Adelaide River in the Northern Territory fear shot down my spine. Silently, an immense Saltwater crocodile (Crocodylus porosus) weighing around a ton suddenly appeared along side our aluminum dinghy piloted by croc scientist Grahame Webb. Webb let loose a string of expletives at the monster and poked it on the snout with an oar. It vanished with a swish of it immense tail. (4. Saltwater crocodile, submerged except head) Mostly nature is more benign, like a platypus at dawn quietly working the water along a shallow bank by probing under rocks to find small aquatic organisms on Shoalhaven River in New South Wales. I’ll always remember peering out from my small tent in the middle of the night during a pounding Tasmanian rainstorm to find the scratching sound I’d heard was a small bedraggled wallaby asking for a handout.

Locating the wild places: Australia is a huge country. I visited about 300 parks and conservation areas in Australia while researching my book. I was lucky because early on I encountered a group that humorously called themselves the “Outdoor Mafia.” They were clearly not part of any organized crime. Their bond was cemented in a deep appreciation and knowledge of wild places in Australia. Joc Schmiechen was my initial contact. At the time he was teaching outdoor education in Adelaide. He had intimate knowledge of all the best wild areas in South Australia and had developed an incredible network of contacts that took in much of wild Australia. He generously showed me around or set me up with people who were experts on everything from kangaroo management to poisonous snakes and the remotest parks of the Kimberely. It was through Joc that I met the Coultard brothers, two Aborigine men who were respectively superintendent of Gammon Ranges National Park, and an expert on Aboriginal art. The Coultards cleared a space in the back seat of their landcruiser and allowed me to tag along through remote areas well off any beaten track, meeting with Aborigines and cataloging rock art sites. I also visited place well off the beaten path such as the islands in the Thorny Passage between Adelaide and Port Lincoln. From a naturalist’s perspective these islands were extremely rich in rare wildlife such as the Pearson Island Rock Wallaby, jet black Tiger Snake, White-Bellied Sea Eagles, Ospreys and Australian Sea Lions.

I interviewed Dick Smith, the founding publisher of Australian Geographic, who compiled a list of the top wild places in Australia and the best ways to access them. His top ten was only different than mine in prioritizing the choices. He made his conclusions after piloting his helicopter the entire 25,760 km (16,288 mile) coastline with diversions inland to explore high interest natural areas.

On the usual tourist routes you’ll meet plenty of people from faraway places, but if you get off the beaten track you’ll find most of Australia is uninhabited. As odd as it may seem a long list of spectacular parks or conservation areas were void of other humans during my visits. That’s right, I was the only visitor. On this list were Mootwingee NP (now Mutawintji NP) Litchfield NP, Sturt NP, Fitzgerald River NP, Hammersley NP (now Karijini NP) much of the Cape York Peninsula north of the Daintree Rainforest, the many parks in New England and much of Tasmania. At the time of my initial visits in the l980s about 17 million people lived in all of Australia, a country about 80 percent the size of the United States. The population has changed since then but Australia is still far less populated than most countries.

Cities: Australia has its bright lights. The Sydney ferries on a balmy night are uniquely romantic conveyances as they purr across tranquil waters to dozens of Sydneyside destinations. As the ferry glides along you feel protected by a caressing breeze on your face, dark still water and the irregularly shaped shoreline of bright lights that include skyscrapers, restaurants and homes. Melbourne, Adelaide, Brisbane and Perth have their clean and special ambiences too. Australia is often referred to as “The Lucky Country.” To be sure Australia has its problems, but compared to anywhere else Australia ranks at the top of the world’s best places to be and its cities have lower crime rates than like-sized cities.

NEW SOUTH WALES: where today’s Australia began

The European settlement of Australia started as an English prison colony in 1788 in what today is Sydney, the gateway city to most foreign visitors. Plan to stay in Sydney long enough to enjoy the ferries, restaurants, museums, and historic buildings. If it is winter head southwest and ski Thredbo, Perisher or Charlotte Pass in the Snowy Mountains and, if it is summer, still visit the Snowy Mountains and hike to the summit of Mt Kosciuszko (highest place in Australia 7,310’ [2,228m]). Try birding in the geologically dramatic Warrumbungles where many threatened bird species are found, and hike the trails of New England’s forest parks. Or if you visit when the inland areas are relatively cool, go to the historic mining center Broken Hill, rent a car and visit the kangaroo-rich, big-sky parks. Start at Mungo NP, which is the site of the oldest human remains in Australia, dating back 40,000 years, its lunettes, plus plentiful populations of emus & Western grey kangaroos (Macropus fuliginosus).

Head north to Kinchega NP on the Darling River. Western grey kangaroos, inland parrot species & water birds of many kinds are everywhere. Next is a long dirt road from Broken Hill to Mutawintji NP (formerly Mootwingee NP). The amount of animal life I saw here rivaled anywhere I visited. Head for the Mootwingee Gorge and you should find Aboriginal rock art sites (ancient ochre paintings), the entertaining Yellow-footed rock wallaby (Petrogale xanthopus), Wallaroo (Euro) kangaroos (Macropus robustus erubescens) Wedge-tailed eagles (Aquila audax), large flocks of budgies (Budgerigar melopsittacus) and Little corellas (Cacatua pastinator). Top off your fuel in Tiboobura and continue on to Sturt NP. You’ll find a vast area with immense vistas and the stronghold of the Red kangaroo (Macropus rufus), Australia’s largest macropod. If you leave your car to photograph the large males alongside the road be warned: when I did this I actually had a male as large as a man puff up, flex its powerful chest muscles and come hopping directly at me. I retreated back into the safety of my car. Once inside I noticed female “roos,” who had been out of sight lying in the high grass, stand up and hop away. Apparently the male, now standing three feet from my car staring intensely at me, saw me as a threat to the females or he just didn’t like humans with cameras. Unlike many places in Australia the large “reds” in Sturt have little fear of people. Visit the historic restored sheep stations and don’t forget to pity the poor sheep that lived here and died by the tens of thousands in cycle of constant drought.

.jpg)

NORTHERN TERRITORY: the heart of the Outback

This is wild and dramatic Australia, with the two most celebrated national parks: Kakadu & Uluru (known also as Ayers Rock). Kakadu NP is Australia’s answer to the African Serengeti. Kakadu has an abundance of life in the forms of exotic birds, rare wallabies, dingoes, monitor and frill-neck lizards (Chlamydosaurus kingii), immense Saltwater crocodiles and centuries-old Aboriginal rock art (in ochre & other natural mediums) throughout the rocky escarpment. Make it a must to take a Yellow Watters open boat tour of the river system and adjoining wetlands. If it is anything like my experience you’ll be astounded at the intensity and mix of bird life and should see large goannas and crocodiles hunting. Make it to “the centre” where you can camel trek near Uluru NP (Ayers Rock) and Kata Tjuta (the Olgas). Both of these iconic geological formations are best appreciated at sunrise and sunset.

QUEENSLAND: land of natural treasures

Tropical Queensland possesses the greatest diversity of world-class ecosystems in Australia. It has tremendous botanical diversity and impressive concentrations of wildlife, especially birds, like red-tailed black cockatoos (Calypthorhynchus banksii), man-sized, intimidating flightless cassowaries (Casuarius casuarius), and dozens of species of colorful lorikeets and kingfishers.

Carnarvon Gorge is in the interior and usually reached by light aircraft from Brisbane. On one of my visits we had to fly low over the landing strip to disperse the cattle grazing on it before we could actually put down. Carnarvon Gorge is Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Lost World.” There are superb hiking trails, crystal clear streams and waterfalls, plentiful Aboriginal rock art, and at night Sugar Gliders (Petaurus breviceps) appear out of nowhere and glide from tree to tree in search of sugary sap. There are appropriately named King ferns (Angiopteris evecta) with eighteen-foot long fronds, small wallabies on the rock outcrops, platypus in the streams and dingoes looking for a meal. As you take this in you are surrounded by constant bird noises. The eerie call of the Pied-currawong (Strepera versicolor) is a constant reminder that you are somewhere you’ve never been before.

Fraser Island is an immense cigar shaped sand-island covered in rainforest and heath. It is one of the last places you can find pure dingoes (Canis lupus dingo), not the dog/dingo hybrids that are common on the mainland. The island also features crystal clear “perched lakes.” First-time visitors may find themselves under water when walking into a lake without realizing the glistening sandy bottom is 30 feet below the surface. In the ocean channel between the island and mainland you can find dugongs (Dugong dugon), a creature closely related to the manatee. South of Brisbane is Lamington Tops with a weeks’ worth of hiking trails in the coastal tropics, rich in bird life, small marsupials and rushing streams.

Queensland is flanked by the Great Barrier Reef with both over-developed and pristine continental and coral islands, which are described in great detail in the book. A diver could spend a lifetime on this reef system and only have a rudimentary understanding of how the immense system sustains so many species. Hinchinbrook Island near Cardwell looks like the island in the King Kong movie starring Jessica Lange. Above Cairns is the Daintree Rainforest with its cucuses (Phalanger mimicas) and tree kanagroos (Dendrolagus lumholtzi & bennettians). When you think you’ve glimpsed a monkey moving through the treetops rest assured it is a tree dwelling kangaroo or possibly a cuscus.

Cape York Peninsula: Further north, between the tiny town of Laura and Thursday Island off the northern tip of the Cape York Peninsula, one can still find well-preserved unusually large post-contact Aboriginal art galleries on the rock faces and it is possible to attend authentic Aboriginal corroborees with participants from the remotest areas of the York Peninsula and Northern Territory dancing reenactments of Dreamtime beliefs. Immense Lakefield National Park offers a frontier experience that features river systems populated with Saltwater crocodile (Crocodylus porosus) an ultimate apex predator capable of drowning a water buffalo. The lowland forests of the Cape York Peninsula are home to birds also associated with New Guinea located only 93 miles away, across the Torres Straits. One of these is the striking Palm Cockatoo (Probusciger aterrimus), a black parrot sporting bright red sideburns, with a huge beak and Mohawk-like topknot. There are also eight species of kingfishers, eleven kinds of pigeons and doves (many of them colorfully marked) and more than a dozen species of frogs.

Recently, three new animal species were discovered in the rarely visited Melville Mountain Range. Two of them are truly unique: The Leaf-tailed gecko has a leaf-like appendage instead of a tail and the Boulder frog lives in huge boulder fields where it lays eggs in rocky crevices. The tadpole develops in the egg-sag and hatches as a “froglet,”. Predators are kept at bay by the adult male frog acting as a sentry.

SOUTH AUSTRALIA: somewhat off the tourist track

Wildlife-rich Kangaroo Island a safe haven for many creatures no longer found on the mainland. Isolation and evolution have created new versions of animals on the seldom-visited islands of the Thorny Passage like the venomous jet-black, over-sized tiger snake (Telecopus semiaunalatus) on Hopkins Island. On these islands you can share beaches with parrots and Australian sea lions (Neophoca cinerea) while watching White-bellied sea eagles (Haliaeetus leucoguster) pluck fish from the sea just off shore. The ancient Flinders Ranges are steeply tilted synclin8es. Here I watched wedge-tailed eagles (Aquilla audox) attempt to snag very agile Yellow-footed rock wallabies (Petrogale xanthopus) as they darted over steep rock surfaces on their way home from a morning of foraging at the base of the mountains. In the Gammon Ranges flocks of Major Mitchell cockatoos (Lophochroa leadbeaten), one the world’s most beautiful parrots (pink with a dramatic red and yellow crown), landed in trees over my head and screeched and cackled as I set up camp. Adelaide is a cosmopolitan city, offering culture and many fine wines from the surrounding valleys.

TASMANIA: temperate rainforests & Tasmanian devils

The island state of Tasmania is an hour south of Melbourne by air. Much of Tasmania is wilderness with vast areas of temperate rainforests, large lakes, rushing rivers, snow clad peaks and the world’s largest surviving marsupial predator, the Tasmanian devil (Sacophilus harrisilli). The first time I heard one scream, I was startled out of a sound sleep and found myself sitting up in my sleeping bag with a pounding heart, not knowing what I was hearing. Tasmania is a backpacker’s dream. Best treks are Mt. Field NP, Cradle Mountain-Lake Saint Clair NP (Overland Track), Walls of Jerusalem, and Frenchman’s Cap. Hobart is a wonderful small city with a picturesque waterfront and plenty of good eateries.

VICTORIA: spectacular alpine and coastal parks & the Grampians.Victoria is roughly the size of California and its rural areas sometimes feel and look like California. Melbourne is a sophisticated, well-run city with a world-class arboretum, museums, restaurants, and entertainment. The Age is among the best newspapers in the world. Some nearby areas have unique places to interact with wildlife: French Island State Park (koalas), Healesville Sanctuary (a well-run private zoo originally founded by naturalist David Fleay, who was the first to have platypus breed in captivity). More than 1,700 animals are residents and are exhibited in, generally excellent settings for both the photographer and the animal.

Victoria’s alpine areas are rich in tradition and natural beauty. This is where The Man from Snowy River was filmed. The daredevil horsemen portrayed in the film are real; they came from the area around Mansfield and are known locally as “mountain horsemen”. Horse back riding on the mountain trails is a favorite recreational pursuit here. Skiers can enjoy both downhilland cross-country. The best skiing & mountain parks are: Mt. Buller, Mount Buffalo National Park and Bogong Highlands & Falls Creek in Alpine National Park. The penguin “parade” takes place every evening on Phillip Island when the fairy penguins (Eudyptula minor) waddle from the water up into their burrows. The Grampians, 225 km (139 mi.) west of Melbourne, is rich in mountain wildlife, the best Aboriginal rock art in southeastern Australia & a wide variety of plants adapted to harsh winter conditions and fire. From time to time the park is devastated by raging brush fires that occur regularly throughout mountain areas. The Laughing kookaburras (Dacelo novaeguineae) and koalas (Phaswlarctos cinereus) are easily approachable in the Grampians. The Fairy wren (Malurus cyaneus), is common here and hard to miss with its iridescent blue mantle and constant movement.

WESTERN AUSTRALIA: a very big diverse place. The Southwest portion of this immense state is a botanist’s wonderland with 5,710 native plant species, many of which are found nowhere else. August and September are usually the best time for viewing. The Jarrahaland Wildflower Trail and the Southern Wonders Wildlife Trail offer automobile access to the flowering areas. Explore the wild Kimberley and Buccaneer Archipelago from the comfort of Broome, a pearling town, which offers an exotic but laidback lifestyle including camel treks along the beach. Check out the dolphins at Monkey Mia and dive with the Whale sharks (Rhincodon typus) off Ningaloo Reef. Experience the good life in Perth and Freemantle.

WRITER’S NOTES

A dream assignment: Writing Adventuring in Australia was a life changing experience. I immersed myself in Australia and came to view it as a parallel universe to northern California where I grew up and still live. Americans and Australians share a similar language and culture. However, when comparing ecosystems and wildlife it is only a slight exaggeration to say the life forms seem to be from different solar systems. I finished my writing, confident of my ability to handle big projects in far away places. I delighted in the challenges presented by the task.

Distances & ways of travel: All totaled I traveled about 60,000 kilometers (40,000 miles) in Australia. Along the way I tried my luck with, camels, horses, trains, buses, a wide assortment of watercraft (dive boats, racing sloops, canoes [called Canadians in Australia] kayaks, car ferries, people ferries, rubber rafts & schooners), buses, city rail systems, airplanes of all shapes, sizes and vintages, and the work horses of my travels, the rental car.

Initial contact as a magazine writer: Before this book assignment, I went to Australia as a magazine writer covering topics ranging from how U.S. farm subsidies affected wheat farmers in Australia to stories on how to best manage aggressive man-eating Saltwater crocodiles (Crocodylus porosus) in Queensland and the Northern Territory. (Actually women had been eaten at a ratio of about 6 to 1 at the time of my visit.) The crocodile story led to explaining the unique evolution of the egg-laying, milk-producing platypus (Ornithorhynchus anatinus), and how this peculiar mammal survived unchanged in Australia’s waterways for tens of thousands of years. Next came its fellow monotreme, the spiny Short-beaked echidna (Tacchyglossus aculeatus), a gentle creature with observable endearing behavior including the gentle treatment of their highly dependent young called “puggles.” And, so it went. There was always another interesting story. Because the animals were so exotic and unfamiliar to Europeans and North Americans, my story would always find a home. Articles appeared in: International Wildlife, Pacific Discovery, Animals, San Jose Mercury News (Travel), San Francisco Examiner (Science), Llamas Magazine, California Farmer, Town and Country (Australia), and Llama Life.

Adventuring in Belize by Eric Hoffman, First Edition 1994

Sierra Club Books, San Francisco, 371 pages, ISBN 0-87156-592-7

After the publication of Adventuring in Australia, the editors at Sierra Club Books asked me to write another natural history travel guide. After my experience in Australia, which was both exhilarating and ultimately exhausting, I figured I’d be better off traipsing around a much smaller country. So, Adventuring in Belize became my next Sierra Club assignment

Size of Belize, its language and population: With the goal of avoiding the tyranny of distance, Belize was the perfect fit. Belize measures a mere 70 miles wide (112 km) and 180 miles long (289 km). Its main natural features are a barrier reef stretching the length of its coastline and vast pristine lowland tropical rainforests with parks, conservation areas, and Mayan ruins. The country is populated by an interesting mix of cultures (Creole, Garifuna, Mayan, Hispanic, Mennonites, Ex-pats from the UK, US, Germany, Australia & Jamaica). Belize is the only country south of the United States in the Western Hemisphere whose official language is English.

A snapshot of Belize: Just imagine nursing a beer as you stretch out in a hammock strung between two coconut palms on a sandy cay littered with conch shells. The sparkly aqua-blue water laps at a ribbon of beach. (1a Emma Gill) Territorial crabs (Cardisoma quanhumi) stand at-the-ready on the beach every ten meters or so holding their biggest pincher skyward as an advertisement to other crabs. Overhead two Magnificent frigate birds (Fregata magnificens) with seven-foot wingspans ride the breeze effortlessly. Their forms are unfamiliar to most North Americans. Magnificent frigate birds glide on long, narrow, and angular wings that allow them to literally remain entirely motionless while aloft facing into a gentle breeze. Their heads swivel ever so slightly, scanning the shoreline for the opportunity to snatch a meal. They position themselves as sentries above the activities of other avian hunters. Frigates are parasitic hunters that hope an osprey (Pandion haliacetus) happens by to pluck a fish from the sea so they can dive bomb and harass the osprey until it drops its catch. The lightning-fast, highly maneuverable frigate then snatches the plummeting fish before it splashes back into the sea. Their agility in the air usually keeps them well fed and their acrobatic style is always exhilarating to witness. As you watch the frigate birds, it is common to see an old wooden fishing sloop in the distance, tilting in the breeze its tired yellow sails bulging, carrying precious cargo of lobsters, or who knows what, to Belize City.

Usual tourist route: For most visitors Belize consists of flying to the international airport retrieving your luggage and transferring to a small plane for a 15 minute flight to Ambergris Cay for a week of scuba diving, birding and island hopping. With so many great dive sites and islands to visit this can be an entirely fulfilling experience. It is still the most common path of tourism through Belize.

Diversity of options: Relaxation and Belize can be synonymous terms. In my time there I completed more than sixty scuba dives. The Blue Hole, Dory’s Channel, Lighthouse Reef, South Water Cay, Placencia, the Sapodilla Cays and Hol Chan were all memorable experiences. The area is also known for its cave dives. They are dangerous and should only be attempted by skilled divers. There is much to see on land too. The trails in the Cockscomb Basin are exciting and carry a special tension. Watch for the tracks of a Jaguar. More than 60 of these magnificent cats live here.

Climb through the immense Mayan ruins at Caracol. Watch for the striking iridescent ocellated turkeys (Meleagris ocellata) foraging through the nearby underbrush. It requires a little perseverance to get to southern Belize and the town of Punta Gorda, but if you have the time and inclination, go, hiking the trails to Mayan villages in the area will be an unforgettable experience.

In strife torn Central America Belize is a breath fresh air, but it isn’t without problems. The government wrestles with the pressure of immigrants from nearby countries, and from the drug trade that influences much of the power structure in neighboring countries. In Belize City gangs and aggressive panhandlers are a reality. The rural areas and islands are generally laid back and trouble free. Be advised traveling in mixed groups is safer than traveling alone especially for women.

Challenges of travel on the island: Internal travel in Belize is often an adventure, be it on single or double prop airplanes or a school bus fronting as a commercial bus. Flying in small planes in Belize assumes a casual ambience. More than once I was asked to carry my luggage on my lap to help balance a plane’s load. One island landing strip I visited featured several wrecked planes just off the runway. On the coast, ocean-going over-sized speedboats, are the transport of choice. These boats make good time to offshore dive sites and faraway islands. On land options range from rental cars to the very inexpensive, nationwide bus service whose fleet includes “retired” US school buses, some with their place of origin still emblazoned on their sides. I rode in buses sporting the logos of “Billings, Montana” & “Boise, Idaho”.

Cockscomb Wildlife Sanctuary: Conservation areas such as the immense Cockscomb Wildlife Sanctuary (originally set aside as the first ever Jaguar Preserve) are as wild and as rich in wildlife as anywhere on the planet. Five species of wild feline live in the Cockscomb: jaguars (Panthera onca), ocelots (Leopardus pardalis), mountain lions (Puma concolor), margays (Leopardus weidii), and jaguarondis (Puma yagouaroundi). The place is also rich in bird life and mid-sized mammals like tayras (Eira Barbara), coatimunidis (Nasua nasua), agoutis (Dasyprocta punctata) and a transplanted group of endangered Black howler monkeys (Alouatta pigra) that have flourished after being moved from northern Belize.

Mayan ruins: The country has dozens of significant Mayan ruins, some of them only partially excavated and still not often visited by tourists. The largest is Caracol, which once dominated better-known Tikal across the border in Guatemala. In many ways Lamanai posseses the best ambience and is the most thought provoking because of its beginning that predates the Mayans. Xunantunich, which has a great temple top vista of central Belize, is right off the Western Highway. Generally the ruins in the southern Toledo District are smaller but unique and not often visited. If you go this far south visit Lim Ni Punit, Lubaantum, and Uxbenka. All these sites are different from one another and surrounded by lush vegetation with plentiful wildlife.

Belize Zoo: Former trapeze artist Sharon Matola created this unique zoo from discarded animals once used in a movie set. The animals are well cared for and housed in natural settings. Visiting this zoo is a feel good experience and a rewarding stop for photographers who want good quality animal photographs in a natural setting. Matola runs an educational program for school children. The program has changed the attitude towards native wildlife throughout the country. The zoo is located on the road from Belize City to Belmopan.

“…As a manufacturer myself, reading this book opened my mind and helped me better understand the importance of good breeding and the effects it has on fiber products we offer. … I highly recommend the second revised edition of The Complete Alpaca Book as the bible for alpaca owners and breeders, and as a fountain of knowledge for alpaca aficionados around the world.”

Derek Michell, CEO Michell & CIA

The Complete Alpaca Book, by Eric Hoffman, First edition 2003, Bonny Doon Press, Santa Cruz, CA, 604 pages ISBN 0-9721242-0-9.

The Complete Alpaca Book, Second revised edition, 2006, Bonny Doon Press, Santa Cruz, CA, 619 pages, ISBN 0-9721242-1-7; 978-0-9721242-1-8.

The Complete Alpaca Book, second edition, revised provides factual information for veterinarians and owners. The book has over 6oo pages, 1,350 references, 250+ tables and figures, 500+ photographs and 3 color sections. Primary author and editor Eric Hoffman gathered 14 coauthors from five continents to create the most comprehensive resource on camelids ever written.

Chapters & Authors:

“Natural History and Ecology”, “Alpaca Anatomy and Conformation”, “Behavior and Communication”, Geriatric Alpacas”, “Fleece Preparation and Shearing”, “Restraint”, “Taming and Training”, “Alpaca Husbandry - Farm Layout, Fencing, Shelters”, “Poisons”, “Shows”, “transportation”, “Fiber Processing, Characteristics & Nomenclature” – Eric Hoffman

“Nutrition & Diet” - Robert J. Van Saun, DVM, MS, PhD, Dipl ACT /ACVN (revised)

“Breeding to Improve Fleece Quality” - George Davis, MagrSc, DSc

“Reproduction and Neonatology” - Ahmed Tibary, DMV, PhD, Dipl ACT

“Medicine and Herd Health” - Ty McConnell, DVM

“Parasitology” - Stuart White, PhD, Karen Baum, DVM

“Diseases: Infectious and Noninfectious” - Linda V. Carpenter DVM, Robert P. Ellis, PhD, Juliet Gionfriddo, DVM, MS, Denis Ryan, MVB, MRCVS (expanded coverage now includes Nancy Carr, MD writing on Bovine Viral Diarrhea Virus (BVDV) and Chris Cebra VMD, MA, MS, DACVIM of Oregon State University. Dr. Cebra is renowned for his work in combating Hepatic Lipidosis and many maladies related to digestion and the processing of food.)

“Husbandry & Care on the Altiplano” - Rufino Quilla, DVZ

“Basic Genetics & Breeding”, “Coat Color Genetics “- D. Phillip Sponenberg, DVM, PhD

Background: The Complete Alpaca Book took two years to assemble, write and edit. The effort represents my passion for the subject and a fortunate convergence. I had been around the camelid scene 30 years and had collaborated earlier on The Alpaca Book with Dr. Murray Fowler, DVM. Knowledge about the physiology, reproduction, husbandry, diet and fiber production of camelids increased rapidly in the 1990s. During this time I was editor of The Alpaca Registry Journal, a peer reviewed science publication sent to all owners of registered alpacas in North America. The editor role allowed me to become better acquainted with university based researchers and veterinarians around the world who specialized in camelid medicine. I worked closely with many of these people and knew firsthand about how well they could explain what they know.

I also helped design the screening protocols that were used to determine the acceptable physical, phenotypic and fiber characteristics of alpacas selected for export from South America. I helped train screeners at Oregon State University and was one of a dozen screeners (most of whom were veterinarians) who traveled to South America to evaluate many thousands of alpacas for export to registries worldwide. My work in the Andes put me in contact with fiber mill owners, small and large breeders in Bolivia, Chile and Peru, plus university researchers involved in camelids. This exposure and my fascination with camelids allowed me to develop a greater understanding of the alpaca’s role in South America and its potential in the world. In addition, I had been writing articles for camelid and science publications since l979. These factors coalesced; the time was right to publish The Complete Alpaca Book.

14 co-authors: We recruited camelid experts from Australia, Canada, Ecuador, New Zealand, Peru, and the United States to share their specialized knowledge. We knew we had the best people for their respective chapters but our editorial challenge was to create a text that was consistent in terms of style and readability. We wanted a text that could be understood by the average breeder, but at the same time we did not want to ‘dummy down’ the information.

My wife Sherry Edensmith was the organizational coordinator and managing editor. Not only did she wade through the seventeen chapters I produced, she also worked with all the contributing authors to create a consistent text.

Authoritative resource: We are heartened by positive feedback from alpaca owners and veterinarians around the world who find the book an invaluable resource. The information presented in a number of chapters pushed the ball far uphill from where it had been prior to publication. “Chapter 9, Feeding the Alpaca” by Robert Van Saun is seminal work. Robert’s presentation integrated the research from South and North America into a single text. Ahmed Tibary’s coverage of male and female reproduction, obstetrics, and neonatal care provides hands-on guidance and academic insight. Phillip Sponenberg’s thoughts about color genetics, and genetics in general, offers a knowledgeable treatment of the mysteries of color genetics in alpacas. Who better than Chris Cebra, to write on digestive disorders in camelids? Cebra is the head of camelid research at Oregon State University’s school of veterinary medicine, the longest standing camelid research program the United States. Stuart White put forth extraordinary effort in describing the transmission and prevention of sarcocystosis in camelids.

Influencing fiber production: “Chapter 10: Fiber Processing Characteristics, and Nomenclature” has had an impact on the alpaca business in many countries. Luis Chavez, the general manager of Inca Tops in Peru stated: “Traditionally the alpaca textile sector has not had important participation in the breeding of this species. As a result of efforts like the one made by Mr. Eric Hoffman, a huge potential was discovered in the industry through engagement with the producers in order to achieve substantial improvement in fiber quality, resulting in better prices for producers and more comfortable garments.”

This chapter was enhanced by contributions from Robert Stobart PhD, Angus McColl and Christopher Lupton PhD from their first-of-its kind comprehensive study for the parameters of huacaya fiber characteristics. F.J Wortmann from Aachen, Germany and Lee Millon from U.C. Davis contributed electron microscope and other types of imagery showing the comparative scale structure of suri and huacaya alpacas, vicuna, guanaco, llama, cashmere, Superfine merino, Angora rabbit, Mohair and numerous other specialty fibers. The revision also includes histograms that include mean curvature, percentage of medullation, and spin fineness. The heads of the largest textile mills in Peru explain the fiber characteristics that are the most important for the commercial processing of alpaca fiber. Lastly, Juan Pepper, who is in charge of international sales for Michell & CIA (worlds largest alpaca processor), explains the intricacies and powerful forces that determine value in alpaca fiber garments throughout the world.

(See “Book Reviews” on this website for more about The Complete Alpaca Book Revised Second Edition)

THE ALPACA EVALUATION: A Guide for Owners and Breeders a handbook, DVD and CD setby Eric Hoffman with Sherry Edensmith and Pat Long DVM. Bonny Doon Press LLC, 2008, 120-page handbook, 2 instructional DVDs, 1 evaluation form CD, 3 leg angulation templates.

Evaluate your own animals: This ambitious undertaking shows alpaca owners how to use proven objective criteria to gain essential information for making informed husbandry, breeding, buying and selling decisions.

A transparent system: Using objective criteria to assess an alpaca’s value can inhibit hyperbole, cheating or glossing over negative traits. Anyone can use the evaluation form to check an animal’s structural soundness, phenotypic characteristics, and take their own fiber sample for a current histogram to determine fiber quality.

3 hours of DVD instruction:

Filmed in Peru and North America by Silverwood Productions, The Alpaca Evaluation has accurately been called the “stay at home seminar” because viewers can access a diverse group of experts from around the world at the touch of a button, and revisit them anytime the need arises.

Using criteria developed in 1996, and used worldwide, Pat Long, DVM and Eric Hoffman demystify alpaca evaluation sharing in-depth information on the objective evaluation techniques for phenotype characteristics, body condition, teeth, jaws, eyes, ears, airflow through nostrils, spinal and reproductive systems, locomotion, leg soundness, heart, hernias and fiber. A compilation of video clips and still images illustrate a wide range of characteristics that may be found in an evaluation. Following their hands-on demonstration, scores are explained to help owners utilize their evaluation results.

Dr. Jane Wheeler explains alpaca prehistory, and the development of fine fleeces.

From Arequipa, Peru, Derek Michell, Juan Pepper and Narcisa Quispe Tanca offer a multi-faceted portrait of fiber processing and international marketing.

Eric Hoffman gives a hands-on comparison of South America’s camelid breeds and species.

Interviewed on site in the Peruvian highlands, Rural Alianza President, Jose Gomez and Dr. Jose Apaza explain the breeding and fiber goals of the world’s largest alpaca operation.

Angus McColl takes you behind the scenes at Yocom-McColl Testing Laboratories, Inc. to watch the creation of a histogram.

The Alpaca Evaluation Handbookis a fully referenced 120-page text with more than 150 color photographs, tables, graphs, and illustrations. Expanding on the evaluation techniques shown on the DVD, the handbook explains what to look for, why it is important, and presents the history and ongoing scientific discussions of the evaluation criteria. Scoring, and considerations for using evaluation results are included in each chapter.

Transparent templates are included to allow precise measurement of leg angles, as demonstrated in the DVD.

The Alpaca EvaluationForm CD simplifies scoring and record keeping. The icon based format makes the technical language of the original screening evaluation user-friendly. The authors have created an evaluation tool that can be understood in any language and used by anyone.

Writer’s Notes:

Additional applications for objective evaluations: In addition to being adopted by registries around the world (mostly in the national herd acquisition phase in new alpaca countries), some of the evaluation standards were used to create the stud certification program in Australia, the expanded screening program of Alpaka Zucht Verband Deutschland, and evaluation standards adopted by the Peruvian government. Information from the forms has also been used as documentation in legal proceedings.

A record of objective measurement is a valuable tool. In this case it can be a universal tool because the basic tenants of objective evaluation have been used in nearly all alpaca populations in the world.

Making objective evaluation user friendly: We used the talents of graphic artist Iris Laudig to create an easy to use icon-based format for the comprehensive alpaca field evaluation developed for the Alpaca Registry Inc. (ARI) in 1994 at the University of California at Davis and Oregon State University. Evaluators match images on the forms to parts of the animal. A total point score is determined by adding the physical exam and fiber scores. Imported alpacas needed to score at least 80 of 100 points to be accepted into a registry. This system was adopted, and sometimes modified, by registries around the world.

The US and Canada abandoned screening and closed their registries to imported animals only a few years after screening was first introduced, (creating captive domestic markets). Others continued to use screening criteria for importations, for stud certification or ranking their national herd. Alpaca evaluations of this kind improved the foundation stock around the world.

For each evaluation, permanent identification (implant or tattoo) must be verified and recorded. Evaluation catagories: Points may be awarded in each of the following areas:

Species indicators (phenotype characteristics): ear shape, muzzle length and shape, adult withers height, adult weight, tail set and fiber characteristics.

Physical exam of: head (dentition, eyes, ears, shape of muzzle, wry face, restricted air flow [possible partial choanal atresia]), body condition (indicator of health), spinal system (including the tail), leg conformation (long bone abnormalities (degrees of angles in legs) including defects of the foot, such as fused feet, polydactylism etc.) reproductive organs, heart, hernias, locomotion abnormalities, and evidence of parasites.

Approximately 100 congenital defects have been identified in alpacas and most of them are detectable by an experienced evaluator. Serious defects can compromise an animal’s health, reproductive potential, life span, quality of life and value, and may be passed on as inherited traits. Some leg defects are “gradient defects” ranging from slight to severe. Greater point deductions are taken for moderate and severe defects.

Fiber quality: Sixty-percent of the evaluation’s 100 possible points are awarded for fiber, the alpaca’s most important by-product. A score is determined from a fiber sample, taken at the time of evaluation, sent to a laboratory, tested with approved I.W.T.O technology, and rated in a histogram, showing fineness, deviation, prickle factor, curvature and other characteristics important to fiber processing. The fiber score is not an opinion, (except for density, which is evaluated subjectively on the live animal); it is based on histogram results.

Scoring: Working from a possible 100 points (105 for super density in huacayas), the system allocates 60 points for fiber, and 40 for the combined physical and phenotype scores. Instead of ranking animals based on “oral reasons” like those given in the show ring, this form of evaluation provides a comprehensive written record and can be reviewed for accuracy.

Evaluation Tools: The tools needed for this field exam include: evaluation forms, clip board and pen to record findings; a scale for weighing livestock and a measuring device to determine withers height; your hands for palpation (feeling the jaw, spine, legs, feet, abdomen and sexual organs to detect abnormalities and assess fleece density and body condition); calipers for measuring dentition/palate alignment and sexual organs; transparencies with angles on them to accurately record the degree of angulation in legs; a narrow walking area to allow observation of an alpaca’s straight-line walking motion to detect locomotion and structural defects, a small flashlight to examine eyes, a sharp scissors or shears to collect a fiber sample, and zip lock sandwich bags to preserve the labeled fiber samples so they can be sent to a fiber testing laboratory.

See “Reviews” for more about The Alpaca Evaluation: A Guide for Owners and Breeders. To purchase a copy, or watch DVD excerpts of evaluation techniques and interviews with world experts click here.

Screening Handbuch fur Alpaka Zucht Verband Deutschland von (written by) Eric Hoffman, ubersetzt von (translated by) Dr. Uli Lippl, Auflage uberarbeitet von (revision editor) Mike Herrling, Alpaka Zucht Verband, Deutschland e. V., 2007, 68 pages.

This handbook was created to help one of the leading alpaca registries in Europe train veterinarians and breeders to give screening exams. Though altered somewhat for the German registry, the system relies heavily on objective criteria that originally appeared in The Alpaca Book, The ARI Screening Manual, The Complete Alpaca Book, The Alpaca Registry Journal, British alpaca magazine and other publications. The Germans used screening to select animals for importation and to rank them in their national herd.

In 2005 I was hired by Alpaka Zucht Verband Deutschland (AZVD) to create a German training manual, and teach new screeners.Pat Long DVM, my long-time screening companion was hired to teach German veterinarians. The original screeners (made up of US & Canadian vets and lay screeners) were trained and tested at Oregon State University in l994. As time passed attrition diminished the number of screeners available. Ironically the US and Canadian registries closed their populations to imported stock while the rest of the alpaca world continued to enhance their foundation herds with imported alpacas. German interest in objective evaluations and the way it is being used in Germany established a new level of refined assessment.

I went away from four years of training impressed with the German eye for detail, dedication to learning, and sense of humor. The Germans did their reading assignments, asked detailed questions and always showed up to seminars well primed for what was on tap. They came from all walks of life, from east and west Germany: doctor, retired fighter pilot, veterinarians, soldier, professors, pedigree horse farmer, trout hatchery operator, trucking contractor, students, martial arts instructors, plumber, and more. Their only common trait was a desire to learn to evaluate alpacas. Fortunately, everyone spoke English, a real gift to this American who speaks only irregular Spanish and passable English.

Under the organizational tutelage of Mike Herrling, participants were held to a high level of accountability before they were certified. Their knowledge was tested in both written tests and numerous rigorous field evaluations. The system was used on imported alpacas and as a means to track the frequency of congenital problems and fiber characteristics in the AZVD registry.

The Alpaca Book: Management, Medicine, Biology and Fiber, by Eric Hoffman and Murray Fowler DVM Clay Press, 255 pages, First edition 1995, Second printing 1997, ISBN 0-9646618-0-2

The Alpaca Book was the first referenced text for alpaca owners outside of South America. This 255 page, 22-chapter book has 303 footnotes. It was written to help alpaca owners understand and care for their alpacas, which were seen as exotic animals, having only been imported into North America since 1984.

Authors: At the time of publication, co-author Murray Fowler DVM was a professor at the University of California Davis School of Veterinary Medicine (UCDSVM). Known “the father of zoo animal medicine,” Dr. Fowler was one of the four founding professors at the UCDSVM. As llamas and alpacas grew more popular, he spearheaded seminars to educate veterinarians and owners.

Eric Hoffman had been involved in camelids for almost 20 years. In l979 he crossed the Sierras and climbed Mount Whitney with his llama Sunny. He was involved with alpacas from the time of the first importation to North America in 1984. He was co-creator of the blood type/DNA based Alpaca Registry that was set up to track lineage and keep the llama and alpaca gene pools separate. He published numerous articles on all six species of camelids in regional and national magazines.

Content: We attempted to bring existing knowledge of alpaca biology and management into a single volume. We saw the book as a stepping stone, written to help new alpaca owners who were trying to raise animals in conditions where they were exposed to new diseases, diets, predators, and climates challenges. A desire to help meet these challenges, and a genuine appreciation for the alpaca were our inspiration.

We reported the current knowledge from South America, Australia and Europe on all aspects of fiber assessment, production and processing, to aide breeders in developing this valuable product.

The Alpaca Book sold briskly through two printings in the l990s. Some of its content was used to identify good quality alpacas based on their phenotype characteristics, physical conformation, and fiber quality in the screening protocols that were created for inbound alpacas from South America. The system is objective in nature and relies on a comprehensive exam in which findings are recorded in precise terms. The screening protocols were adopted by alpaca registries around the world and influenced the quality of alpacas imported into the North America, Australia, and Europe.

A good start: This book was an excellent first step in helping veterinarians and breeders understand this new form of livestock. As our knowledge and understanding about the unique physical and behavioral characteristics of these fine fleeced animals grew, I knew there was a growing need for another, more comprehensive, resource so with the help of a diverse and distinguished group of experts; I wrote one. The first edition of The Complete Alpaca Book was published in 2004, and a revised 2nd edition was released in 2006.

ANNAPlease put in a LINK to the Complete alpaca book

Renegade Houses by Eric Hoffman

Running Press, Philadelphia, 1982, 153 pages,

ISBN 0-89471-181-1 (paperback) ISBN 0-89471-181-2 (library binding)

This was my first book. When literary agent Marti Sternberg found a publisher for it I thought, hey, writing for a living is a real possibility. Looking back I was pretty naïve. I still had a lot to learn about the publishing business. I was teaching high school English at the time and found myself under the gun with a publication date that only gave me four months to complete the project. My rush resulted in some avoidable “surprises” in photo selection and layout. Happily, Tam Mossman my editor was pleasant, skillful and fast.

Simple formula - avoid the suburbs: Renegade Houses was a wonderful project that deserves to be reborn in more detail highlighting the new technologies that exist now. The original formula was simple; let twenty different people tell the story of how they developed their own living spaces. Pick people whose homes are entirely unique. Something not found in America’s suburbs was my mantra. The stories that tumbled forth were daring, innovative, usually well thought out, sometimes a little loony, but always a point of pride to the builder. There was no end to people wanting to share their stories, even if they had to use an alias to avoid detection from their local building inspector. The technologies included ancient techniques such as daub and wattle as well as unconventional new-age approaches like compacted rammed earth wall construction, and sculpting a super strong, waterproof, free form home built with ferro-cement. The ferro-cement building, known locally as ‘the periscope house,’ looks like something cartoon character Barney Flintstone would’ve called home.

Recycle & salvage: With most builders there was an emphasis on recycled materials, and in some cases recycling a building in its entirety. Structures ran the gamut in terms of costs. Some were made entirely from salvage. Others were state of the art architecture from their respective era but needing extensive retrofitting (abandoned warehouse loft in San Francisco, decommissioned rural train depot).

Saving a rural train depot: The train depot was more about moving a building than constructing one. The critical moment in this project was finding an available parcel of land near the depot where it could be moved without a great deal of complication. When an adjacent lot was procured just out of the railroad’s right-of-way, professionals moved the old station intact. As a result an early classic l9th century Southern Pacific Railroad station began a second life as a bed and breakfast with manicured gardens. The building was purchased for $1.00.

Building codes: The homes presented Renegade Houses were both legal i.e., fully permitted by the appropriate governmental entity and illegal i.e., built off the grid in a remote area. The variety of approaches was astounding, for example, a tree house sitting sixty feet off the ground on something the builder called a “slip foundation.” The tree house’s “foundation” was a rafter system built in the shape of triangle that hung from three trees whose trunks held the building aloft and defined the corners of the platform as an equilateral triangle. Spied for the first time this system of suspension looked both clever and precarious. It lasted about 25 years before it came tumbling to the ground during a powerful winter storm. As luck would have it, nobody was in it when it collapsed.

Recycling an old church: A favorite of mine was tearing down an old church marked for demolition and rebuilding it as a house. After paying $1,500 with a promise to remove the church in a month, builder David Brower proved to be meticulous even working under a time crunch. He numbered each board so it would be in the same position when the building was reassembled as a two-story house featuring the original structure’s spectacular clear heart redwood trusses.

Subterranean house: Incorporating passive solar principles found in the ancient Anasazi cliff dwellings of the Southwest, a mostly-buried passive solar house on the California coast blended prehistoric and modern technology. Deer were often unaware that the slope they were grazing on was only superficially part of the surrounding grasslands. They were actually standing on the building’s sod roof that merged seamlessly into the hillside.

Modified yurt: In the original form a yurt is an easy-to-assemble mobile living space made mostly of skins and felted cloth tied to a circular frame. Yurts were invented by Mongolian nomads before the time of Genghis Khan and are still in use today in remote areas of central Asia. The yurt in this book is a hybrid made of pre-assembled trapezoidal wedge-shaped wall panels placed around the circumference of a circular plywood subfloor. Two sturdy cables cinch the wedge-shaped panels tightly together, one running at the base of the wall while the other runs through the top of the wall. Once the perimeter wall is tightened and secured the ceiling’s rafter system can be quickly assembled. Though the rafter-panels are more pie shaped than the walls, they are also held together with one perimeter cable. The roof system’s layout resembles the spokes of a bicycle wheel. In the bicycle wheel all spokes converge at the axle at the wheel’s center and are further apart as they reach the wheel’s rim. In the yurt all rafters converge at the “o ring” suspended over the building’s center and spread further apart as they reach the outer wall. Once the cable that snakes through the outer reaches of the rafters is tightened, the pie-shaped rafter-panels become compressed into a sturdy whole. The foundation and subfloor were straightforward: rows of concrete piers and girders 4’ o.c. covered in 1 1/8” plywood. When the joist system and plywood subfloor are in place the walls and ceiling can be assembled in a day. This yurt takes a little longer to assemble than the original Mongol model, but its wood and cable features assure it will last.

Building with dirt. Adobe bricks made of mud and straw are low cost and can last for centuries. A number of the original eighteenth century adobe Spanish missions are still standing in earthquake prone California. Adobe is rigid and not particularly strong. Rammed earth construction, is much stronger than mud bricks. Although the main building material for this type of construction is the dirt nature provides at the construction site, it is analyzed and amended to increase its strength before being pounded into thick, rock-hard walls, held in place by reinforced concrete “I” beams.

Creativity & thinking outside of the box: There is little doubt that the living spaces described in Renegade Houses would be more difficult to construct now, 30 years later. Raw property prices have spiked, fallen and are trending upward again. Building departments and ordinances are more tightly written, with more penalties and less wiggle room. However, when it comes to living space thinking outside the box has its place in a world manipulated by banks, mortgage companies, insurers, & ordinances. Sweat equity can still result in dividends and a hassle free home. Thinking creatively, mustering the drive, and doing-it-your way, while soberly understanding and considering the risks, will always have its place. The downside to this type of thinking is if everyone did it ‘outside the box’ we would plunge into living space chaos. Rest assured everyone won’t attempt to literally make their own home. For one thing, the need to conform is instinctual to most of us. For another thing it is hard work. Is it worth it? For some, the answer will always be yes.

Writer’s Notes:

Endorsements: Serendipitously, several high-profile people were enthusiastic about my undertaking, and agreed to endorse the book. After reading the manuscript, Bob Judd, then co-director of the California Office of Appropriate Technology for Governor Jerry Brown wrote: “This book is an anthem to the American spirit. It gives substance to words like ‘inventive’ and ‘resourceful’ and ‘practical’…”

Rock star Joe Cocker, also lent his name. “This book shows house-building can be as creative and fun as music making. The only limitation for both is lack of imagination.” I met Joe when I was interviewing a homebuilder who happened to be his friend. He unexpectedly rode up on his bicycle and was immediately curious about the project. Two months later he phoned at 2:00 A.M. to say he liked the concept, but wanted to know why, since “renegade” was in its title, the book didn’t have a dwelling representing Native Americans. He caught me flat-footed. I stammered and offered that the Mongolian yurt was somewhat representational of a native people’s dwelling. To my relief he changed the conversation to his music, and ended our conversation agreeing to endorse the book.

Langdon Winner, the author of Autonomous Technology and contributor to Atlantic Magazine and Rolling Stone wrote, “It’s about time someone told the story of people who solve their housing problems in novel ways. This book shows that American ingenuity is alive and well in the works of these owner builders.”

The book was favorably reviewed by the San Francisco Examiner, Philadelphia Enquirer, Publisher’s Weekly and other publications.

Salmon and Steelhead, the Struggle to Restore an Imperiled Resource,

edited by Alan Lufkin, University of California Press, 288 pages, first edition 1990. ISPN 978-0520070295

“Saving the Steelhead” by Eric Hoffman first appeared in Monterey Life, a glossy magazine serving the Monterey Bay area. In Lufkin’s book the article appears as Chapter 30. It received much more attention from its inclusion in the anthology than it ever did in a regional magazine. It is about the success of dedicated volunteers overcoming challenges and joining forces with a logging company to establish a fish hatchery to restore steelhead in creeks north of Santa Cruz California, where they hadn’t been seen in years. The group is applauded for releasing 350,000 fish. The article’s strength was in capturing a moment in time when traditionally antagonistic groups (logging & conservation) voluntarily joined forces with a heartfelt commitment to restore a species to its historic environment. I will always remember this story. I arrived at the hatchery in the costal mountains north of Davenport California, to interview biologist David Streig on January 28, 1986. Just as I pulled into the hatchery the music on my car was interrupted with an announcement that the space shuttle Challenger had exploded shortly after launch and the crew was presumed lost. Streig and I stood there for a few moments absorbing the tragedy. I was dumbfounded, and though David Streig and I had just met the expression on his face told me he was upset too. We slowly moved into a discussion of his program. I was initially distracted as he explained anadromous fish biology, but as I listened his enthusiasm became uplifting. He gave a soliloquy of sorts about his love for the handful of returning female salmon he called “his girls” and he talked convincingly about the importance of restoring salmon and steelhead to nearby streams. Without a pause in our conversation he waded into a nearby creek, pushed some floating debris aside and stooped so low in the water I thought the water would pour down his chest and fill his waders. He groped under a snag, pulled out a large silver fish and posed for a picture. Streig was in his element and looked the part with his large body, full beard, plaid shirt and chest-high waders. His eyes glistened with tears as put the fish back under the snag. Decades later, when I saw the Harry Potter character Hagrid I recalled David Streig, The two seemed to be cut from the same cloth.

The Best From Monterey Life,

Monterey Life Magazine, Monterey, CA., 244 pages, 1990.

Nine of my articles were chosen for inclusion in this hardcover tenth anniversary anthology. In all, the editors selected 24 articles that best “celebrated nature and the environment.”

“They’re Back” by Eric Hoffman.

This article celebrates the diversity of Monterey Bay’s marine mammals & the challenges they face.

“The Brown Bomber” by Eric Hoffman.

Merges my childhood memories, of idyllic summer days watching Brown pelicans diving for fish and moves on to explain the species’ comeback from the ravages of DDT. Scientist at UC Davis who were studying the birds’ problems with the deadly pesticide provided information and data.

“Where Eagles No longer Dare” by Eric Hoffman.

Kudos to avian veterinarians Craig Rouse, Donald Petkus and the Ventana Wildlife Society for their dedication to the care of badly injured bald eagles. Alaska Airlines airlifted injured eagles from Alaska to the clinic in Monterey California without charge. In many cases the doctors were able to release the birds back into the wild.

“Ghost of the Condor” by Eric Hoffman.

These giant gliders from the Pleistocene all but disappeared in the l980s. Though it was controversial at the time, the only hope for species survival was through captive breeding using the few remaining birds. This article focused on the program’s shaky start and the intense pressure put on the recovery team’s leader Noel Snyder. The narrative becomes a story about perseverance and the multi-institution effort it takes to save an imperiled species. The critics either wanted a solution in months for a problem that was over a century in the making, or they were willing to let the condor slip into oblivion as an example of mankind’s poor stewardship. Today wild condors can once again be seen riding the thermals above Los Padres National Forest, the Pinnacles National Monument, The Grand Canyon and in Baja California.

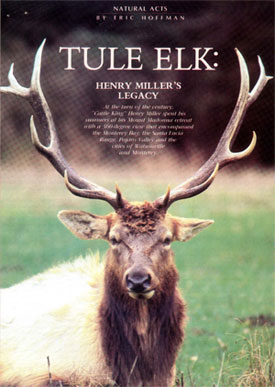

“Tule Elk: Henry Miller’s Legacy” by Eric Hoffman.

19th century cattle baron Henry Miller’s steadfast protection of the last Tule elk, discovered on one of his immense ranches in 1874, allowed the animals to survive. Today, the elk are found throughout the state, mostly commonly in California’s state parks.

Henry Miller was the quintessential laissez-faire capitalist, who arrived in California nearly broke and made his money first as a butcher, later as a cattle baron whose cattle went to slaughter to realize a profit. Yet, when it came to saving the Tule Elk, another part of his personality revealed itself; that of an animal rights conservationist, far ahead of his time.

“Plight of the Peregrine”by Eric Hoffman.

As well equipped as this falcon is for survival, it isn’t equipped to cope with a poisoned environment. The article celebrates the bird’s design for speed, its fearlessness while hunting, and successful efforts to breed them in captivity for release into the wild.

“A World Class Arboretum” by Eric Hoffman.

With over 9,000 plant species, including unsurpassed collections of plants from Australia, New Caledonia and New Zealand, the UC Santa Cruz Arboretum is indeed, world class. This article chronicles the history of the arboretum, from its unbudgeted beginning as the shared vision of Dean McHenry and professor Ray Collet to the present. Meeting Dean McHenry, the first chancellor of UCSC, while researching this article was a pivotal moment for my writing career. (See “Mentors”)

“The Delicate Survivors” by Eric Hoffman.

Thousands of beautiful monarch butterflies congregate in Pacific Grove and Santa Cruz each winter. Scientists are mystified by how monarchs navigate their long distance travels and the irony of over-wintering in eucalyptus trees, a non-native species they apparently like just fine.

“Loving the Critters to Death” by Eric Hoffman.

This article reminds us how dangerous it can be for wild creatures when humans habituate them to handouts.

Craftsman-Style Houses by Fine Homebuilding.

Tauton Press Inc., Newton, CT., 159 pages, 1991 “An Estate in Bonny Doon” by Eric Hoffman

Used as a chapter, my article describes a spectacular Craftsman-style mountain retreat sitting 1000 feet above the Pacific Ocean. It describes the techniques used to make the exuberant free-flowing granite stone work that covers exterior walls and chimneys. In the house’s interior, the commitment to detail is exemplified by the use of custom templates to create precise trim joinery that locks in place. The house sits in a meadow on the edge of a redwood forest. The use of redwood and stone on the exterior walls combined with a slight green tint applied to the steeply pitched shingle roof, allow the house to blend into the forest. The article first appeared in “Fine Home Building” magazine.

Writer’s Notes:

Being part of anthologies: In addition to books, magazines or blogs, the anthology is an often neglected venue that can extend the shelf life of your writing and increase your visibility as a writer. If something you’ve written is tapped to be part of an anthology chances are it will be read long after it was first published and may develop a life of its own.